Organ Recital – April 28, 2025 – 8:00pm

Works for the Organ Inspired by Gregorian Chant

Presented by Carlos Foggin, FRCCO, B.Mus

Knox United Church, Calgary AB

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M.Mus (Performance) at the University of Calgary

Programme

Balbastre: Concerto en Re Majeur (10’)

Willan: Fantasia upon the plainchant melody 'Ad coenam agni' (5’)

Frescobaldi: Messe della Madonna from Fiori Musicali (16’)

Langlais: Epilogue from Homage à Frescobaldi (6’)

Intermission

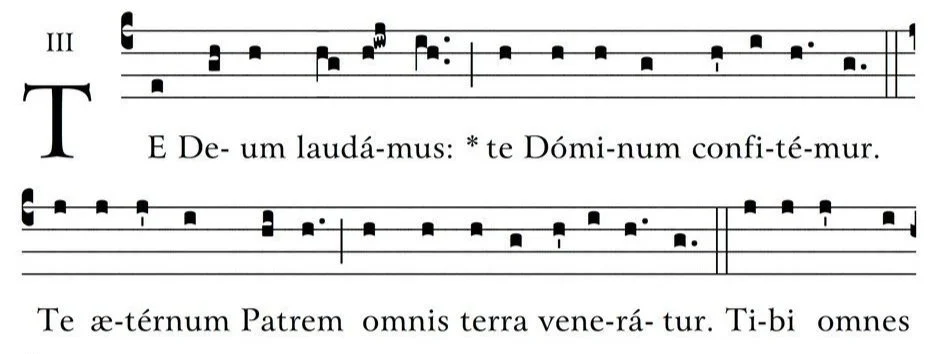

Tournemire: Improvisation sur Te Deum Laudamus (7’)

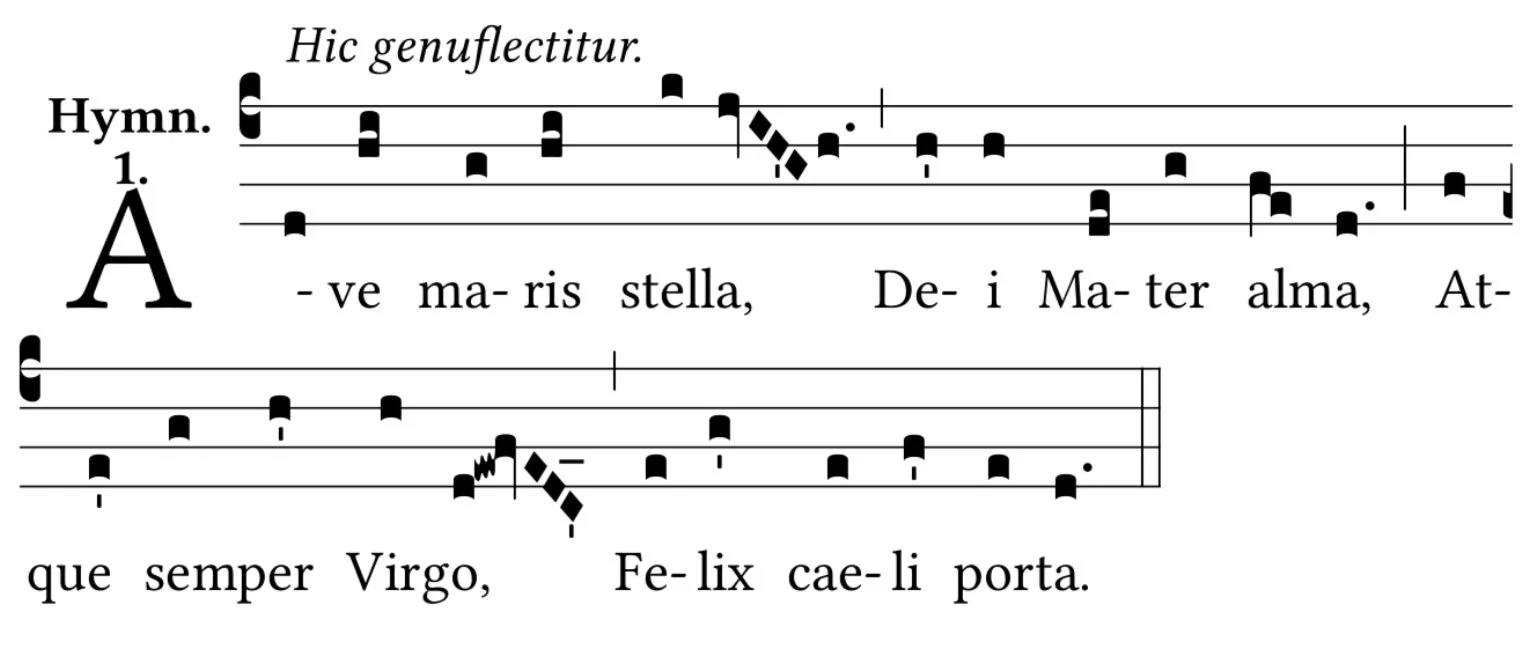

De Grigny: Ave Maris Stella (10’)

Guilmant: Variations et Fugue sur le chant du Stabat Mater Dolorosa (13’)

Balbastre: Concerto en Re Majeur (1749)

Prélude

Allegro

Duration ~ 10 minutes

Claude-Béninge Balbastre (1724-1799) was one of the most celebrated French keyboard composers and performers of the 18th century. Renowned for his virtuosic organ and harpsichord playing, Balbastre served as organist at Notre-Dame Cathedral and later at the royal court of Louis XV. His music—marked by elegance, brilliance, and charm—bridged the late Baroque and early Classical styles. A favourite of Parisian society, he was admired for his improvisations and his innovative use of ornamentation and colour. Balbastre’s works include harpsichord pieces, organ noëls, and liturgical compositions that remain admired for their flair and inventiveness.

In 1733, the organ at Notre Dame was enlarged by François Thierry. The organ was expanded to 49 stops over 5 manuals, and a new façade that still exists today. In 1783, Cliquot rebuilt the organ. Though extensively rebuilt and expanded in the nineteenth century by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll in the 1860’s, some of the original Clicquot pipework was reused, notably in the pedal division of that instrument, where it continues to be heard today. At the time of it’s installation, it was the largest instrument in the Kingdom of France. The Cliquot specification is detailed below.

As they were used primarily for treble solos, the récit and écho divisions were short compass (they didn’t have all the bass notes). Interestingly, the two short compass manuals have very similar specifications, but would have been voiced very differently. Quick manual changes in the second movement (Allegro) will demonstrate the effectiveness of this particular layout.

A typical organ in the French Classical Style tended to have very small pedal divisions (often only an 8’ flute), and the presence of a 32’ stop on the manuals is virtually unheard of. For tonight’s performance, I have only utilized the stops that would have been available on this historical 1783 instrument; however, this doesn’t mean a weak sound - in fact, quite the opposite! Despite the wealth of fantastic options here at Knox, some sounds (such as multiple Cornet stops, and the Gross Nasard and Tierce) have fallen somewhat out of fashion, and are not available. However, not all is lost! Through the magic of sub and super couplers (which allow manuals to be coupled to each other at an octave above or below the note played), we are still able to re-create the sound of the 32’ Montre, as well as the Double Nasard and Double Tierce on the Grande Orgue, a real sonic treat!

Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris – Cliquot (1783)

I. Positif

C-d3 sans Cis

Montre 8’

Bourdon 8’

Prestant 4’

Flûte 4’

Nasard 2 2/3’

Quarte 2’

Doublette 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

Plein-Jeu VII

Cornet V

Trompette 8’

Cromorne 8’

Clarion 4’

II. Grande Orgue

C-d3 sans Cis

Montre 32’ (from La 22’)

Montre 16’

Bourdon 16’

Montre 8’

Bourdon 8’

Flûte 8’

Double Nasard 5 1/3’

Prestant 4’

Double Tierce 3 1/5’

Nasard 2 2/3’

Doublette 2’

Quarte 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

Gross Fourniture V

Gross Cymbale IV

Fourniture IV

Cymbale III

Grand Cornet V

Gross Trompette 8’ 2e

Trompette 8’

Voix Humaine 8’

Clarion 4’

Trémblant

Pos/GO

III. Bombarde

fixed coupler to Grande-Orgue

Bombarde 16’

IV. Récit

C1-D3

Cornet V

Trompette 8’

V. Écho

f-d3

Cornet V

Cromorne 8’

Pédale

F-d1

Grosse Flûte 8’

Flûte 8’

Gross Flûte 4’

Flûte 4’

Bombarde 16’

Trompette 8’

Clarion 4’

GO/Ped

Frescobaldi –‘Messa della Madonna’ from Fiori Musicali (1635)

Toccata avanti la Messa

Quatri Versetti sul Kyrie

Kyrie Eleison

Kyrie Eleison

Christe Eleison

Kyrie Eleison

Canzon dopo l'Epistola

Ricercar dopo il Credo

Toccata avanti il Ricercare

Ricercar con obbligo di cantare la quinta parte senza suonarla

Toccata per l'Elevazione

Duration ~ 16 minutes

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi (1583-1643) was one of the most important renaissance and baroque keyboard composers and virtuoso musicians of his time. Born in Ferrara into a musical family (it is suggested that his father may also have been an organist, and it is known that his half-brother, Cesare, was), he studied under Luzzasco Luzzaschi and was twice appointed as organist of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. His large musical output includes music for both vocal and instrumental ensembles, though it is for his keyboard works that he is rightly most famous. Eight collections of keyboard compositions were published during his lifetime, with more either published after his death, or passed on to future generations through the original (but unpublished) manuscripts. His two books of toccatas and partitas (1615 and 1627), alongside his last published and only religious work, the Fiori Musicali (1635) from which today’s performance is taken, are his most important outputs. The 1615 book of toccatas contains works that could be used in liturgical situations and were designed to either be used as introductions to other pieces or, for those amongst them of a grander scale, as substantial works in their own right.

The set contains three organ masses and two secular works. This set of works is the only one in his output devoted solely to a directly religious context, and each contains music set directly on the plainchant themes of each of three diferent Kyriales (musical settings of the ordinary of the mass): Messa della Domenica (mass for Sundays, or Kyriale XI, Orbis Factor), Messa delli Apostoli (mass for the Apostles, or Kyriale IV, Cunctipotens genitor Deus, and finally, for the performance today, Messa della Madonna (mass for Our Lady, or Kyriale IX, Cum Jubilo). This work dates from after the important Caeremoniale Episcoporum of Pope Clement VIII in 1600, codifying the liturgical decisions of the Council of Trent, which set out the use of the organ to replace alternate verses of the mass ordinary (so they were not sung by the choir); however, this new style was never adopted in Italy at the scale or with the enthusiasm it had been in France. In Fiori Musicali, the organ replaces the voices only in the first sung part of the mass, the Kyrie eleison (Lord, have mercy).

Generally acknowledged as one of Frescobaldi's greatest works, Fiori Musicali (musical flowers) influenced composers during at least two centuries. Johann Sebastian Bach copied it out by hand, and parts of it were included in the celebrated Gradus ad parnassum, a highly influential 1725 treatise by Johann Joseph Fux which was in use even in the 19th century. Scholars widely acknowledge the Frescobaldi’s influence, through Fiori Musicali, on the structure of Bach’s celebrated Clavierübung III.

Frescobaldi admonishes the organist…Before playing, look carefully at the score, it is a very beautiful composition but full of setbacks that you can solve with a deep and careful study "not without effort one reaches the end".

Registration Considerations

Italian organs of this period were typically one-manual, based on warm principal tone, with pitches and mutations soaring as high as the 1’ piccolo. Often, the stops were split into treble and bass chests, so that above and below middle C were capable of varied registrations. Flutes were regarded as a dedicated solo stop, rarely combined with the principals. The undulating fiffaro (a principal celeste) was drawn only with the 8’ principal and played slow music ‘as smoothly and legato as possible’. Importantly, three is the largest number of stops drawn in many lists of registrations, apart from the various big ripieni used only once or twice in a service.

Italian Registration Guidelines from 1615

Ottava 8’ + Flauto 8’, good for quick passages and canzonas

Principale + Flauto in duodecima, good for quick passages and canzonas

Principal + Flauto in quintadecima, good for quick passages

Pedal pipes, good for occational long notes in a toccata

Ripieno: 16 - 8 - 4 - 2 2/3 - 2 - 1 1/3 - 1 - 2/3

Mezzo-Ripieno:

8 - 4 - 1 - 2/3 with flauto in ottava (or)

8 - 4 with flauto in ottava (or)

8 - 4 with Flauta in duodecima

Use half stops for ‘dialoghi’

The Music

There are 7 principal movements, arranged around the typical Italian organ mass order (a toccata for before the mass, five versets for the Kyrie, and pieces for after the Epistle, after the Creed, a pair of pieces for the Offertory, and a final gorgeous toccata for the elevation of the consecrated elements. Although an extra piece or two is sometimes added to round off the mass (a sort of recessional – totally in line with performance practice for an organ mass in Italy), I’ve elected to conclude tonight’s performance of this work as Frescobaldi left it – with the serene Elevation Toccata. So much music, so little time!

1. Toccata avanti la Messa della Madonna (Toccata before the mass of Our Lady)

The toccatas of the Fiori Musicali are rather different to those in Frescobaldi’s earlier keyboard works and, instead of consisting of multiple different sections, are instead rather exquisite miniatures with typical renaissance phrases – gently rising and falling melodic lines. Frescobaldi gives detailed notes to the performer in the preface to the work, noting that the trills should be played expressively, and the tempo should fluctuate, starting slowly at the beginning of passages and gently accelerating as the phrases progress.

2. Kyrie Versets:

ORGAN Kyrie eleison

As is traditional, the organ begins the frst petition of the Kyrie eleison, to which the choir will respond with the second. This short verset is based directly on the plainchant it replaces and all of them are written in an exemplary four-part counterpoint. The plainchant is heard in long notes (as a cantus firmus) and also in the alto part (the second highest of the four) with a countersubject with some unusual chromaticism.

SUNG Kyrie eleison

ORGAN Kyrie eleison In the third petition of the Kyrie, the plainsong of the petition just sung by the choir is heard again in long notes, first in the bass (the lowest of the four voices) before appearing again in the alto and finally in the soprano, the highest voice.

SUNG Christe eleison

ORGAN Christe eleison

Unusually, Frescobaldi provides two organ versets for the Christe eleison, even though only one is needed in the normal alternatim arrangement. In Kyriale IX, there are two musical themes present in each of the three main petitions, the first Kyrie, the Christe, and the final Kyrie. This first of the two Christe petitions is based on the first of the two Christe themes, the one normally sung by the choir, and so isn’t strictly needed. There are some suggestions that occasionally in Italy the order of organ and choir was reversed, with the choir starting, meaning that this switch would be needed. It is also possible that this is simply an additional verse for variety; the other two masses in Fiori Musicali both provide many more verses for the Kyrie than would ever be required in one performance, and this may simply be for variety. The plainchant melody is heard first in the soprano and then the bass, before concluding in the soprano.

SUNG Christe eleison

ORGAN Kyrie eleison

The organ encounters a B-flat for the first time in the first verse of the final Kyrie section (we have heard it previously in the choir, but not yet in the organ). The theme is stated in the tenor, and is then presented in stretto, with the theme (in a clever inversion) presented in the alto.

SUNG Kyrie eleison

ORGAN Kyrie eleison (Lord, have mercy)

The final section, this last Kyrie verset is more musically developed and quicker paced with the motif moving around all voices before the carefully prepared and developed cadence.

Gradual

3. Canzon dopo l’Epistola (Canzona after the Epistle)

This canzona, written for performance after the reading of the epistle, may have been designed to wholly replace the chant of the gradual and alleluia customarily sung at this point of the mass. In this way, it would provide musical “cover” for the liturgical preparation and procession for the reading of the gospel which would follow it. The canzona is in two clear sections using an imitative style between the four voices who each get a form of the main theme (which was used by the Parisian organist Jean Langlais in his 1951 work Hommage à Frescobaldi - coming up later tonight) throughout the piece. This rather sprightly section, in 4/4 time, gives way rather abruptly to a slow adagio section, which provides the link in to the second part of the work where the same theme is used only now in triple-time, but losing none of the brightness that is typical of this movement within the Italian tradition. I’ve interpreted the break between the two sections as a full stop where the Gospel would be read. Following the Gospel, the second section then provides the joyful cover music for the Deacon’s return to the high Altar and the subsequent rite of incensing.

4. Ricercar dopo il Credo (Ricercar after the Creed)

This movement forms the largest and most developed of the work so far, starting with a bold theme that contains a chromatic scale. After a cadence into the major key, the theme moves to form a cantus firmus in long notes in the bass part whilst a second motif appears repeatedly woven around it. It can be considered as a musical response to the text of the creed itself, reaffirming the meaning of the words just sung.

Offertory

5. Toccata avanti il Ricercar (Toccata before the ricercar)

Though the previous movement could be considered part of the offertory, it seems more fitting to consider that that role is performed by the next two movements which, because of the title of the first, are clearly considered by the composer as linked. This opening toccata is highly typical of Frescobaldi, taking only a small amount of musical material and weaving an intricate and delicate web that gains in tempo as it develops with more abrupt motifs that almost hint at the fun that is coming in the next movement.

6. Ricercar con obligo di cantare la quinta parte senza toccarla (Ricercar with obligatory singing of the fifth part without playing it)

This is surely one of the most confusing pieces in this work. It begins with an elegant six note theme, but before the first bar is written, Frescobaldi writes the same six notes, but in a different time signature and metre, saying that this should be sung, but without playing it, and without indicating where within the work it should be sung. There are a number of places where the addition of this fifth part fits within the four-part texture, but it is clearly left up to the performer to work out where these are. If it is to be sung, Frescobaldi gives us no words, though some suggest that the tradition could be to sing “Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis” (Holy Mary, pray for us), or perhaps it would be left to an instrumental musician in the organ gallery. It remains a puzzle to this today, and that is perhaps how Frescobaldi intended it. Naturally, you’re invited to participate – a full score is printed in the program as a guide.

7. Toccata per l’Elevatione (Toccata for the elevation)

The elevation of the host and chalice is the central and most holy part of the celebration of the mass. Amongst the many musical styles that Frescobaldi typifed, his elevation toccatas are perhaps the most famous, and their simplicity and beauty fit this part in the mass perfectly. Composed in the phrygian mode (mode 3), it has an ethereal and other-worldly quality, signifying the arrival of God Himself in the consecration of the bread and wine. It is indicated by the composer to be played slowly, giving time for the congregation to be transported in prayer through its unusual chromatic tonality, strong rhythmic patterns, and filled with suspensions. The softest stops on the organ are used for this single page of immense beauty.

Healey Willan – Fantasia on Ad Coenam Agni (1906)

Duration ~ 5 minutes

Dr. Healey Willan, C.C. (1880-1968) was a composer, organist and teacher. He moved to Toronto in 1913, taking the position of Head of the Theory Department of the Toronto Conservatory of Music. In 1914, he was appointed organist at St. Paul’s Bloor Street, and was appointed Lecturer and Examiner for the University of Toronto. From 1921 until his death, he was Precentor of the church of St. Mary Magdalene. In 1934, he founded the Tudor Singers, which he conducted until 1939. Between 1937 and 1950, he was Professor of Music at the University of Toronto.

In 1953, he was commissioned to write an anthem for the coronation of Elizabeth II and in 1956, he received the Lambent Doctorate, Mus. D Cantaur from the Archbishop of Canterbury.

He composed more than 850 works. More than half were sacred works for choir including many anthems, hymns and masses. His compositions also include secular choral works, songs for voice and piano, two symphonies, a piano concerto, chamber works, and the opera Deirdre.

Many consider Healey Willan to be the "Dean of Canadian Composers". He was made a Companion of the Order of Canada in 1967.

In Ad Coenam Agni, Willian opens with a statement of the the theme in the pedals, echoed in the manuals. A short improvisatory section (repeated 3 times throughout the work) echoes the statements. A solo tuba then exclaims the theme, followed by the improvisatory episodic material. From there, a strict polyphonic section emerges over several pages, steadily building in intensity and volume, demonstrating the seamlessly smooth and powerful crescendo capabilities of an English-style Cathedral organ. The fantasia concludes with an explosive re-statement of the theme, using the powerful high-pressure tubas. A final statement of the theme in the pedals is followed by a short but powerful coda.

The Church of St. Mary Magdalene – Breckels and Mathews (1906)

II. Great

61 notes

Double Open Diapason 16’

Open Diapason #1 8’

Open Diapason #2 8’

Stopped Diapason 8’

Gamba 8’

Octave 4’

Wald Flute 4’

Twelfth 2 2/3’

Fifteenth 2’

Mixture 1 1/3 IV

Cornet V

Trumpet 8’

Clairon 4

Sw-Gt 16-8-4

Ch-Gt 16-8-4

Gt-Gt 4

I. Choir (enclosed)

61 notes

Gedackt 8’

Dulciana 8’

Unda Maris (TC) 8’

Chimney Flute 4’

Spire Principal 2’

Larigot 1 1/3’

Cymbel 1/2’ III

Cremona 8’

Tuba 8’

Tremulant

Sw-Ch 16-8-4

Ch-Ch 16-4

III. Swell (enclosed)

61 notes

Lieblich Bourdon 16’

Stopped Diapason 8’

Salicional 8’

Viola da Gamba 8’

Vox Angelica (TC) 8’

Principal 4’

Suabe Flute 4’

Nazard 2 2/3’

Flageolet 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

Sharp Mixture 1’ IV

Bassoon 16’

Trumpet 8’

Oboe 4’

Shawm 4’

Tremulant

Sw-Sw 16-4

Pedal

32 notes

Sub Bourdon 32’

Open Metal (GT) 16’

Open Wood 16’

Subbass 16’

Lieblich Bourdon (SW) 16’

Octave 8’

Flute 8’

Super Octave 4’

Recorder 4’

Mixture 2 2/3’ IV

Ophicleide 16’

Bassoon (SW) 16’

Trumpet (GT) 8’

Clairon (GT) 4’

Gt-Ped 8-4

Sw-Ped 8-4

Ch-Ped 8-4

Jean Langlais – Epilogue from Homage à Frescobaldi (1951)

Duration ~ 5 minutes

Born in La Fontenelle, Brittany, France, a small village near by the Mont Saint-Michel, Jean Langlais (1907-1991) became blind from the age of two. Sent to the Paris National Institute for the Young Blind in 1918, he studied piano, violon, harmony and organ with great blind teachers among other Albert Mahaut and Andre Marchal. Later, he entered the Paris National Conservatory of Music in Marcel Dupre organ class, obtaining a First Prize in 1930. In 1931, he received the “Grand Prix d’Execution et Improvisation des Amis de l’Orgue”, after having studied improvisation with Charles Tournemire. He ended his studies with a Composition Prize in Paul Dukas’ class at the Paris Conservatory in 1934.

Professor for forty years at the National Institute for the Young Blind, he also taught at the Paris Schola Cantorum where, between 1961 and 1976, he influenced both french and foreign students. In 1945, he became the successor to Cesar Franck and Charles Tournemire at the prestigious organ tribune of Sainte-Clotilde in Paris. He left that position in 1987 at the age of 80, having been titular for 42 years.

In Homage à Frescobaldi, Langlais pays homage to the seventeenth-century Italian keyboard virtuoso and composer Girolamo Frescobaldi most overtly in the eighth movement, "Epilogue." The final movement is an energetic pedal solo, the theme of which quotes Frescobaldi's canzona from the Messa della Madonna, from the Fiori Musicali (1635). Not content with a flurry of single pedal notes (in the style of Bach and his contemporaries), Langlais instead requires the organist to play a fugue, with both feet engaged. As the toe and the heel of each foot can play a note, he often asks for three notes at once – and at a few points, he event writes 4-note chords! With a lot of preparation (at a little luck), the piece is a real showstopper!

The idiom of Hommage à Frescobaldi, is, however, very much within the late French Romantic organ tradition, making Langlais' dedication of the piece to his teacher, Marcel Dupre, scarcely less important than the title itself.

Basilique Ste-Clotilde – Cavaillé-Coll (1859, expanded in 1962)

I. Grand-Orgue

Montre 16

Bourdon 16

Montre 8

Flûte harmonique 8

Bourdon 8

Viole de gambe 8

Prestant 4

*Octave 4 (2)

*Quinte 2 2/3

*Doublette 2

*Cornet V

*Plein-jeu VII

*Bombarde 16

*Trompette 8

*Clairon 4

* jeux de combinaisons

II. Positif

Bourdon 16

Montre 8

Flûte harmonique 8

Bourdon 8

Viole de gambe 8

Salicional 8

Prestant 4

*Flûte 4

*Quinte 2 2/3

*Doublette 2

*Tierce 1 3/5

* Larigot 1 1/3

*Piccolo 1

*Plein jeu harmonique III-VI

*Trompette 8

*Clairon 4

III. Récit (expressif)

Quintaton 16

Flûte harmonique 8

Bourdon 8

Viole de gambe 8

Voix céleste 8

Principal Italien 4

*Flûte 4

*Nasard 2 2/3

*Octavin 2

*Tierce 1 3/5

*Plein-Jeu IV

*Bombarde 16

*Trompette 8

Basson-Hautbois 8

Clarinette 8

Voix humaine 8

*Clairon 4

*Clairon 2

Pédale

Soubasse 32'

Contrebasse 16

Soubasse 16

Bourdon 8

Flûte 8

Prestant 4

Flûte 4

Doublette 2

*Bombarde 16

*Basson 16

*Trompette 8

*Clairon 4

– INTERMISSION –

Charles Tournemire – Improvisation sur Te Deum Laudamus (1931)

Duration ~ 7 minutes

Charles Tournemire (1870-1939) served as the organist at the basilique Sainte-Clotilde in Paris. He was a professor of harmony at the Paris Conservatory and the organist at St. Clotilde (Cesar Franck's church). Tournemire was a student of Franck and went on to teach Langlais, Messiaen and Duruflé. He was a rather interesting individual, known for his moodiness and intense personality. He was a deeply mystical Catholic and was attached to the writing of Ernest Hello. Tournemire was also close to the monks of Solesmes and there in lies the connection.

Tournemire considered a project of compositions based on the proper chants of the Sunday as far back as 1922, when he wrote of his conversations and visits to the Abbey at Solesmes. At this time, the French had just allowed the religious and monks to return to France, after having been thrown out for some years. A new religiosity had been made and the monks at Solesmes were in its midst. Tournemire visited there many times and made much of their singing.

His modern-day claim to fame is his cycle "L'Orgue Mystique", a collection of organ mass settings for every Sunday of the church calendar. However, he was also a celebrated improviser. In 1930-1931 he recorded five of his improvisations for the phonograph. 25 years later, his former student and assistant Maurice Duruflé, by then a highly successful organist and composer, painstakingly transcribed these improvisations; his intimate knowledge of both the organ and the organist allowed him a level of detail rarely seen or surpassed since.

Duruflé's transcriptions are also not completely literal; there a points where even Duruflé couldn't always discern the exact notes, and he even made some additions of his own (although only when it would be characteristic for Tournemire also). Nevertheless, both the improvisations and transcriptions are extremely virtuosic. There is always structure, however; it is remarkable how they sound like written-out pieces. By transcribing them, Duruflé produced an immortal monument to the heights of French improvisation.

Basilique Ste-Clotilde – Cavaillé-Coll (1859, expanded in1933)

I. Grand-Orgue

Montre 16

Bourdon 16

Montre 8

Flûte harmonique 8

Bourdon 8

Viole de gambe 8

Prestant 4

*Octave 4 (2)

*Quinte 2 2/3

*Doublette 2

*Cornet V

*Plein-jeu VII

*Bombarde 16

*Trompette 8

*Clairon 4

* jeux de combinaisons

II. Positif

Bourdon 16

Montre 8

Flûte harmonique 8

Bourdon 8

Viole de gambe 8

Salicional 8

Prestant 4

*Flûte 4

*Quinte 2 2/3

*Doublette 2

*Tierce 1 3/5

*Piccolo 1

*Plein jeu harmonique III-VI

*Trompette 8

*Clairon 4

III. Récit (expressif)

Quintaton 16

Flûte harmonique 8

Bourdon 8

Viole de gambe 8

Voix céleste 8

*Flûte 4

*Nasard 2 2/3

*Octavin 2

*Tierce 1 3/5

*Plein-Jeu IV

*Bombarde 16

*Trompette 8

Basson-Hautbois 8

Clarinette 8

Voix humaine 8

*Clairon 4

Pédale

Soubasse 32'

Contrebasse 16

Soubasse 16

Flûte 8

Quinte 5 1/3

Flûte 4

*Bombarde 16

*Basson 16

*Trompette 8

*Clairon 4

De Grigny – Ave Maris Stella (1699)

Hymn in Alternatim Praxis

Plein Jeu à 5

Fugue à 5

Duo

Dialogue sur les grands jeux

Duration ~ 10 minutes

Organ (Plein Jeu) HAIL, O Star of the ocean, God's own Mother blest, ever sinless Virgin, gate of heav'nly rest.

Choir: Taking that sweet Ave, which from Gabriel came, peace confirm within us, changing Eve's name.

Organ (Fugue) Break the sinners' fetters, make our blindness day, Chase all evils from us, for all blessings pray.

Choir. Show thyself a Mother, may the Word divine born for us thine Infant hear our prayers through thine.

Organ (Duo) Virgin all excelling, mildest of the mild, free from guilt preserve us meek and undefiled.

Choir. Keep our life all spotless, make our way secure till we find in Jesus, joy for evermore.

Organ (Dialogue sur les grands jeux) Praise to God the Father, honour to the Son, in the Holy Spirit, be the glory one. Amen.

Although Nicolas de Grigny (1672–1703) was only thirty-one years old when he died – and published only a single organ work during his lifetime – the Premier livre d'orgue of (Paris, 1699; second edition 1711). The second edition was the only one known until 1949, when the earlier print was discovered - a single surviving copy at Bibliothèque nationale de France. The first modern edition, by Alexandre Guilmant, 1904, was based on the 1711 version.

Nevertheless, he is one of the most influential figures in French Baroque organ music, not least because none other than Johann Sebastian Bach was an early admirer. In 1713, during his time in Weimar, Bach, who probably got to know Grigny's Premier livre d'orgue during his youth in Lüneburg, made a handwritten copy of Grigny's only collection to be published.

Cathédrale Notre-Dame (Riems) – J. Vuisbecq (1696)

I. Grand-Orgue

50 notes

Montre 24’

Bourdon 16’

Montre 8’

Bourdon 8’

Prestant 4’

Flûte 4’

Gross Tierce 3 1/5’

Nasard 2 2/3’

Doublette 2’

Flûte 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

Cornet V

Fourniture V

Cymbale IV

Trompette 8’

Vox Humaine 8’

Clairon 4’

II. Positif

50 notes

Montre 8’

Bourdon 8’

Prestant 4’

Flûte 4’

Nasard 2 2/3

Doublette 2’

Flute 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

Larigot 1 1/3’

Fourniture III

Cymbale II

Cromorne 8’

Trompette 8’

III. Récit

37 notes

Bourdon 8’

Prestant 4’

Nazard 2 2/3’

Quarte 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

IV. Écho

37 notes

Cornet V

Pedale

30 notes

Flûte 8’

Flûte 4’

GO/Ped

Guilmant – Variations et Fugue sur le chant du Stabat Mater op. 65 Nr. 13 (1888)

Duration ~ 13 minutes

Alexandre Guilmant (1837–1911) played a vital role in the development of French Romantic organ music. Born in Boulogne-sur-Mer, he studied with his father and later with the renowned Belgian organist Jacques-Nicolas Lemmens, whose influence shaped his virtuosic technique and liturgical style.

During the four centuries between the Council of Trent in 1563 and the Second Vatican Council between 1962 and 1965, liturgical organ playing in France became highly developed in large part due to the autonomy afforded French bishops to govern the liturgy within each diocese.

The most widely known liturgy used in France was the Parisian Rite, which was used until the middle of the nineteenth century. Accordingly, most French liturgical organ music from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries was written for the Parisian Rite. Eventually the Parisian Rite was supplanted by the more universally recognized Roman Rite. This affected the evolution of the French organ Mass in at least two ways. First was the retention of the “low Mass,” during which the organist played for virtually the entire service, pausing only for the reading and homily as described by Gaston Litaize:

During this era, the organist at the main organ normally played two Sunday Masses:

1) The “Grand Messe,” which involved a processional, an offertory, often an elevation, a communion, and a postlude; in addition, he alternated with the choir for verses of plainchant for the Ordinary (Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, Agnus Dei); they sang a verse and the organ commented on in, changing registrations for each verset.

2) The “Messe Basse,” where the organist could virtually play a recital. With everything spoken in a low voice [“à voix basse,” hence “Messe basse”], this is what happened: the priest left the sacristy, the organist played a procession, which lasted until the Gospel reading, then came the sermon. The organ then resumed and didn’t stop until there was no one left in the church. So, one could easily play a complete Choral by Franck.

Second, with the introduction of the Roman Rite, French organists largely moved away from chant-based organ music, favoring all-purpose Offertoires or Grand Choeurs.

A chant revival movement soon made its mark on French liturgical organ music. In 1889, the Benedictine Abbey of Solesmes published a new chantbook (the Liber Usualis) based on extensive research of early manuscripts that sought to restore chant to its medieval form. Interest in chant revival trickled into Parisian music circles, where in 1894, organist-composers Alexandre Guilmant and Vincent D’Indy founded the Schola Cantorum de Paris. The school’s founding manifesto called for the “performance of plainchant according to the Gregorian tradition; restoration of polyphonic music in the Catholic Reformation style of Palestrina; the creation of ‘new modern Catholic music;’ and improvement of the repertory for organists.” Guilmant in particular championed a return to organ compositions that used chant, writing that, “The German organists have composed some pieces based on the melody of chorales, forming a literature for the organ that is particularly rich; why should we not do the same with our Catholic melodies?”

He was one of the first French composers of his era to use entire Gregorian chants as thematic material in his work. Guilmant’s little-known piece ‘Variations and Fugue on the Stabat Mater’ is strongly based throughout on the Gregorian chant for the Stabat Mater text (At the Cross her station keeping, stood the mournful Mother weeping, close to her Son to the last). It was dedicated to Guilmant’s friend, the famous Paris organist-composer Eugène Gigout, and published in Book 3 of L’Organiste Liturgiste in 1891.

The plainsong melody is followed by a series of eleven short variations on the tune, then by a dramatic recitative which leads into a vigorous fugue based on the theme. The ending of the fugue is absolutely triumphant, suggesting the text of the 20th and final verse of the Stabat Mater – ‘When my body dies, let my soul be given the glory of paradise. Amen’.

Guilmant gained widespread acclaim as a concert organist, performing across Europe and the United States at a time when the organ was emerging as a solo concert instrument. He served as the principal organist at Église de la Sainte-Trinité (stoplist below) in Paris for over 30 years and was later appointed professor of organ at the Paris Conservatoire, where his students included Marcel Dupré and Joseph Bonnet.

Église de la Sainte-Trinité – by Cavaillé-Coll (1869)

I. Grand-Orgue

C-g3

Montre 16’

Bourdon 16’

Montre 8’

Flûte Harmonique 8’

Bourdon 8’

Gambe 8’

Prestant 4’

Flûte octaviante 4’

Nazard 2 2/3’

Doublette 2’

Cornet V

Plein Jeu IV

Cymbale II-IV

Bombarde 16’

Trompette 8’

Clairon 4’

II. Positif

C-g3

Expressif

Cor ne nuit 8’

Flûte douce 4’

Nazard 2 2/3

Flageolet 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

Piccolo 1’

Clarinette 8’

Non-expressif

Quintaton 16’

Principal 8’

Flûte Harmonique 8’

Salicional 8’

Unda Maris 8’

Prestant 4’

Doublette 2’

Cornet II-V

Fourniture IV

Basson 16’

Trompette 8’

Clairon 4’

III. Récit (expressif)

C-g3

Bourdon 16’

Flûte Traversière 8’

Bourdon 8’

Gambe 8’

Voix céleste 8’

Flûte octaviante 4’

Nazard 2 2/3’

Octavin 2’

Tierce 1 3/5’

Cymbale III

Bombarde 16’

Trompette 8’

Basson-Hautbois 8’

Voix humaine 8’

Clairon 4’

Tremblant

Pédale

C-g1

Flûte 32’

Soubasse 16’

Contrebasse 16’

Flûte 8’

Bourdon 8’

Violoncelle 8’

Flûte 4’

Plein Jeu IV

Bombarde 16’

Trompette 8’

Clarion 4’